Ethiopian Imperial Opal

Constellations of Colour - Queen of the Queen of Gemstones, the EMPRESS of Precious Stones.

"Opale Impériale" Français

In 2008 in the high arid mountains of Wollo (Welo) province of Ethiopia a "new" volcanic origin Opal CT (Cristobalite-Tridymite) was discovered. The finest examples of this gemstone are called IMPERIAL OPAL and may be faceted as well as cut in the usual cabochon. They are easily the most rare and most beautiful of precious stones known. Pliny the ancient Roman once called Opal the Queen of gems: Imperial Opal is thus the Empress of Precious Stones. J.D.Sage (Troubadour)

Photography & Comments by Gemologist Gregory Kratch to the Lapidary Journal Editors 2013

The GemGuide

Article by Gemologist Gregory KratchEthiopian Opal

For nearly a decade now, the new find of opal in Ethiopia has been both welcomed and debated on issues of stability and high water content. Some of the material can be quite beautiful and with the quantity that is now available, we need to understand how to handle it better.

The recent discoveries of opal in Ethiopia, and in particular

the finds at Wegel Tena in 2008 have had a

profound effect on the world opal market. Opal is now

more popular than ever. With its astounding brightness,

remarkable new patterns, and unusual physical properties,

this opal is quite different than the Australian opal

which has been the market standard until now. Unlike

the most Australian opal that comes from sedimentary

deposits, the new opal from Ethiopia is mainly formed in

a volcanic environment. Ethiopian opal is classified as

opal-CT. This type of opal is composed of lepisheres or

small balls of crystals of quartz group crystals, tridymite

and cristobalite, which are polymorphs of SiO2, produced

under high temperature and pressure. Australian

opal is classified as amorphous

(opal-A).

Ethiopian opal from Wegel

Tena is a hydrophane, but very

different from the hydrophane

opal of Australia. Hydrophane

opal is porous, and can absorb

water. When Australian hydrophane

opal is soaked in water, it

will absorb some and show a

play of color (often spectacular)

that slowly dims or disappears

when the stone is removed from

the water and dries out. Because

Australian hydrophanes only

show their best play of color

when wet, they are therefore not suitable for jewelry.

However, the Ethiopian hydrophane opals show their

best play of color when dry, becoming more transparent

and less colorful when immersed in water. Once

removed from the water, they will at first become very

cloudy to opaque, and then gradually return to their original

state over a period of a few hours to several days as

they dry out. Stones should not be heated or treated

chemically to speed up this process. This capacity to absorb water and release it with no damage to the stone

is remarkable. Specimens I have tested have varied

widely in their ability to absorb water with stones ranging

from 4% to 15%, based on the dry weight. A gain of

20% was reported by one dealer. Therefore, I recommend

that all opal be correctly identified at the time of

sale so that the owner may properly care for it, and keep

it at its best and most beautiful. The CT hydrophane

opals are very different in many unique ways from what

we have predominately seen in the world market to date

and must be cared for accordingly.

Fig. 1. These two opal rough specimens are from Wollo. While the rough on the left is

spectacular for the pattern and spectrum, the rough on the right shows another side to the

field's potential—natural dark opal form Wollo.Courtesy of Francesco Mazzero/Opalinda.

Stability is always a concern with any opal, especially

with new sources if they have little history. Although

Wegel Tena seemed to offer a new supply of stable opal, there have been incidents of instability, cracking and

crazing. It is imperative to remember however, that all

opal fields produce opal that is unstable. Hungary,

Australia, Mexico and Brazil have all produced their fair

share of unstable material, some of which unfortunately

entered the market. Ethiopia is a whole new frontier. We

will be better able to predict its stability, as we explore

and discover this new source of gem opal. I have found

that once stones were cut, very few have developed any problem. Similar experiences are shared by other experienced

cutters. As the opal industry grows in Ethiopia, I

am sure it will develop the same checks and balances

within the industry itself of reputable miners, dealers

and cutters that hopefully will help keep unsuitable

material out of the trade. No one wants to sell bad opal;

it is not good for your reputation or the industry. It would

be prudent to buy from people who have a longstanding

reputation with opal in the current market and who you

can easily contact if any unexpected problems develop

with your stone. Some

dealers may even offer

time limited guarantees of

up to six months for unset

stones. Discuss any concerns

you may have with

your vendor at the time of

purchase. Everyone wants

a happy customer.

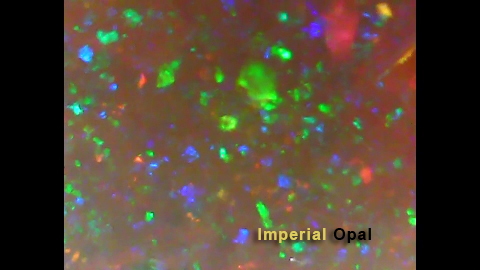

This new opal from

Wegel Tena is also exhibiting

some characteristics

that are quite different and

unique. Rondeau et. al.

published a detailed study

of Wegel Tena opal in

Gems and Gemology Summer 2010. Cut opals from

Mezzezo, Ethiopia and Australia (including a piece of

boulder opal) as well as Wegel Tena were dropped on a

concrete surface from a height of 1.5 meters. The stones

from Wegel Tena showed no damage even under the

microscope. All the other samples showed breakage. Its

unusual durability makes it a great candidate for

faceting, creating stones with kaleidoscopic constellations of color, a whole new avenue to explore. In a different

experiment by Stone Group Laboratories, selected

material from Wegel Tena was subjected to smoke treatment

to darken the stones, with an astonishing survival

rate of 90% despite the high heat and extreme dryness.

The physical structure and hydrophanous nature of the

treated stones, among other things, differentiate them

from natural black Australian opal. Although they are

attractive, they can never rival the finest blacks of

Lightning Ridge.

This remarkable new opal, is quite unlike the

others in many ways. It should be treated, handled

and stored differently as well. I am sure that these

new fields of opal in Ethiopia have many wonderful

surprises in store, and we should welcome

this new imperial addition to the court of the queen of

gem; opal. “…which contains the fire of the carbuncle, the glorious

purple of amethyst, and the sea green of emerald all shining together in

incredible union.”

Historia Naturalis, Vol 37.

Pliny, 23-79 AD

Gregory Kratch is a miner, gemologist, lapidarist, opal

expert and cutter, and a frequent lecturer at the Ecole

de Gemmologie de Montreal.

.jpg)

Dear Sirs,

You published an article in the Lapidary Journal January/February 2012, on the "new" Ethiopian Opal. As I have been cutting this material for years, I wanted to add some of my own observations and experience with this beautiful and very important new discovery, particularly the opal from Wollo Province. As your article correctly noted, this opal is a Hydrophane Opal formed in a volcanic environment. But the differences in formation and physical structure mean that it is not always comparable to opal formed in a sedimentary manner, as is most of the Australian opal. The descriptions in your article of hydrophane and its reaction to light and production of colour in a dry and wet state I consider incomplete in some very important aspects. While it is true that almost all hydrophanous opal will show brighter plays of colour while wet, upon drying, the sedimentary hydrophanes tend to become duller and duller as they dry and the water leaves the stone, their highly porous and irregular structure continuing to interfere with the transmission of the light and consequent production of a play of colour, until the opal may appear almost opaque with virtually no discernable colour.

Unfortunately the article failed to mention that when the opal from Welo (Wollo Province) begins to lose its water content it becomes more opaque or creamy at first, and then begins to clear over a period of a couple days or weeks, if left in a normal environment in a room at normal temperature as the stone continues to dry out. I would not recommend any forced heat to speed up the drying process. Each stone is different. In this way it is similar to the chameleon opal from Java, also formed in a volcanic environment. The Javanese opal also shows its best colour play when it dries out, unlike most opal from sedimentary deposits that look better when wet. And often, even usually, the new material from Wello is more beautiful dry than wet. In the finer near transparent grades I find the slight cloudiness or turbidity in the cut stones, a slight haziness in an almost transparent base, a slight translucence makes them more beautiful and can show more colour than when fully hydrated and completely transparent. It is similar to what happens when you cut a cabochon of very clear crystal opal and put a very high polish on the back of the stone, the highly polished surface allows the light to leave or leak out of the back of the stone with very little light returned to the viewer except the play of colour. However, a soft even slightly frosted finish on the back like a satin 600 surface, scatters some light and lights up the stone better often giving a better more perceptible colour play. In the best Ethiopian material, in my experience, the stones are actually more beautiful when completely dry with a slight haziness to scatter and spread the light around. The entire stone lights up better. Lower and lowest grades, less transparent or opaque opal may be much better when wet. I have limited experience with material of this lower quality. As always with opal, it depends on the individual stone. They are all different, and that's the charm. Often frustrating, but always interesting. The article failed to mention that this new hydrophane opal from Welo would not react like most others, Java excepted, and after an initial period of dulling, when first removed from water and begins to dry out, would then continue to become more transparent and show a better and better colour play as the dehydration continues.

There were other issues I would like to discuss concerning the description of blacks (I have seen a few as well as some beautiful crystal opal on a natural black skin, sort of like a colour bar over a thin black base as seen for example, in some boulder opal, but probably with an iron and manganese oxide crust in the case of the Ethiopian opal from Welo). And base colour and temperature sensitivity as well as iron content and stability are a whole other discussion. I felt it important to write you about the impression your article left that all hydrophanes are only beautiful when wet and lose their colour when dry. This is certainly not the case with the material from Wollo Province.

With the continuing reduction in production of the Australian fields, this new discovery of opal, and in particular, the new opal from Welo, is rapidly gaining acceptance and market share because of it's pure colour and astoundingly bright colour play, exceptional and unique patterns, and just sheer beauty. The Troubadour and Poet J.D.Sage* has dubbed it “IMPERIAL OPAL” the Empress of precious stones. I concur. We should thus enthusiastically welcome this lovely new addition to the royal family of gem opal, the new Ethiopian Imperial Opal, truly an Empress in this family of the Queen of Gems, as Pliny the ancient Roman so aptly described opal, so long ago.

Gregory Kratch

Gemologist

Please follow links to learn more about Imperial Opal (Ethiopia). http://www.jtv.com/library/ethiopian-opal-gia.html

http://www.jtv.com/library/Ethiopian-Opal.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFtesRTeBCk

Opal Evaluation and Correction for Imperial Opal (Ethiopian Opal).

My name is Gregory Kratch. I am a graduate gemologist with the Canadian Gemological Assn. I am also a lapidarist and a specialist with opal. I spent over a decade in Australia in Lightning Ridge mining and at that time was a member of the Lightning Ridge Miner's Assn Evaluation Committee. And I have recently been involved with the new Ethiopian opal from Wegel Tena. I recently read an article from GemA by Samantha Lloyd about opal evaluation. In the article she states that Australian opal contains water and may dry out and crack. She then states that Ethiopian opal contains more water. Now while this may be true under certain circumstances the way the information is presented makes it seem as though with more water, Ethiopian opal's water content would be even more of a problem.I have written two articles, for Lapidary Journal and the GemGuide by Richard Drucker about this new opal and explained the difference between Ethiopian opal and Australian opal. While Ethiopian opal MAY be quite hydrophanous and absorb water, it is very different than Australian hydrophane. Australia also produces hydrophane opal, because of its' nature it is rarely used in jewelry unless filled with resins. It is also amorphous. Ethiopian opal like the opal from Wegel Tena MAY absorb water and sometimes quite a lot( I have tested pieces that took in 15% of their weight.) While some other take in much less and rarely, hardly any at all. It is also not amorphous but composed of fine groupings of tridymite and cristobalite in a framboisoidal grouping(like raspberries) With Australian amorphous opal, when it is hydrophanous, and absorbs water, the water fills the voids in the poorly formed opal and allows the light to exit and show a play of colour that is very weak or not apparent in the stone when dry. As the stone dries the play of cokour dims or disappears completely. However, Ethiopian opal that is hydrophane, shows its' colour best when dry and if wetted, changes, sometimes becoming milky or clear and loses or diminishes its' play of colour when wet. The play of colour returns when the stone is dried out. Exactly the opposite of Australian hydrophane opal. It is a different opal. The volcanic opal from Indonesia reacts the same way. So the fact that Ethiopian opal may contains much more water than the commercial Australian opal we see on the market.,drying out the stone does not have any effect on its' stability. I have even baked cut stones in the toaster oven and the only thing that happened was the play of colour became even brighter. it must be said however that some Ethiopian opal is heat sensitive even when dry, particularly the yellowish stones(iron???) the white and clear crystal is able to take high temperatures without a problem for the most part. This is a wonderful new type of opal and needs to be understood and treated properly and often differently than Australian opal. It is important that people have access to good information and that is why I have written you about this. The article seemed to imply that the fact that Ethiopian opal can take up more water was a bad thing. It is not. I have also enclosed an attachment that delves into these differences that I published with Richard Drucker, Please let me know if you need any more information about this subject.

My best Gregory Kratch

*J.D.Sage (Troubadour) song "What About Me?" Please follow these links to learn more about J.D.SAGE and hear his music and lyrics. "What About Me?" Video (Preview), http://www.cdbaby.ca, http://www.itunes.com, http://www.amazon.com, www.jdsage.com, Video Promotion and also "Internet Highway Cruising Song" Video

SOCAN - MAPL